Introduction

This page documents efforts to lower the firing temperature of David Tsabar’s high-fire Nickel Aubergine.

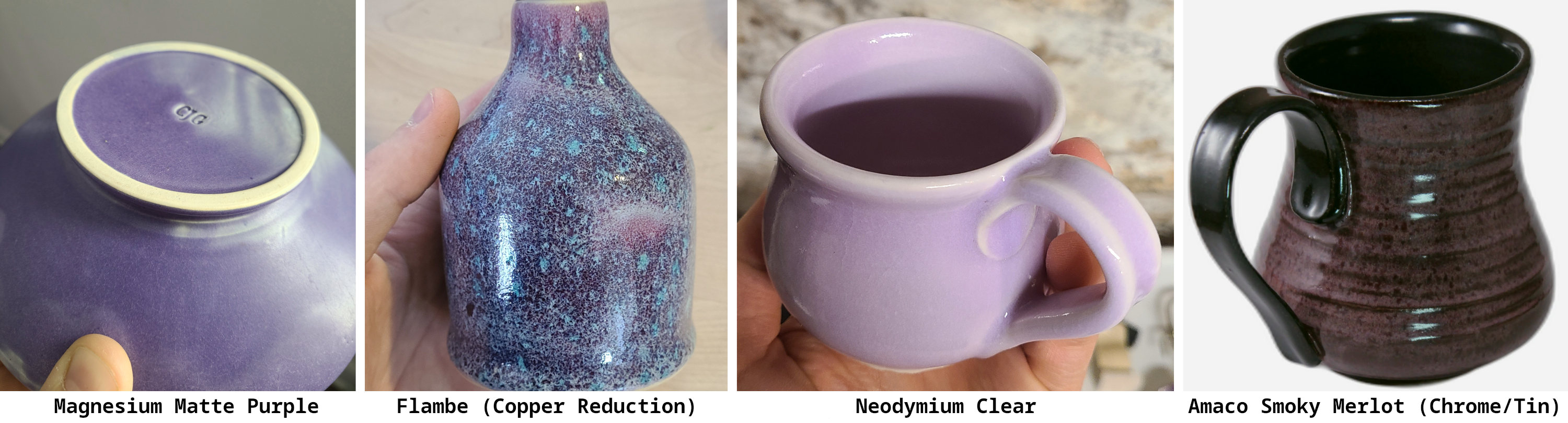

Purple is a tricky color in pottery that can be either trivial or elusive to achieve, depending on your goals.

A matte purple is simple to formulate by adding cobalt to a magnesium matte. An opaque, glossy purple can be done either with encapsulation stain or chrome/tin. Some excellent clear, celadon-like lavenders are possible thanks to neodymium oxide. Beautiful variegated purples appear in reduced copper glazes. But a dark, translucent, glossy purple seems rare among published or commercial glazes.

Initial research points to two possible mechanisms:

- Manganese in an alkaline base

- Nickel in a barium base

There are pros and cons to each approach - overly alkaline glazes craze, while barium is toxic and difficult to work with.

I was interested in a dark, glossy amethyst-purple glaze at cone 6, and began experimenting in early 2024.

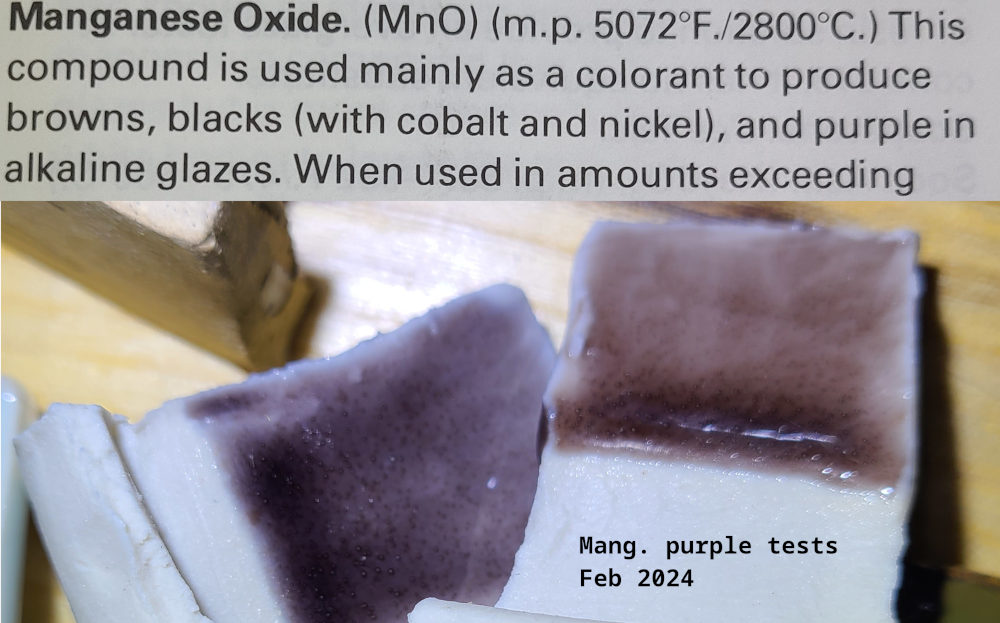

Early Attempts - Manganese

I spent a few months working on the manganese approach. Older literature suggested this was possible, and Sid Henderson was working on a public recipe at the time that offered some photographic proof that it was possible.

After about five experiments I gave up on this approach. I managed to get purple, but it was faint and looked better in photos than in person. The recipe is touchy, turning brown or black with the slightest changes. I never quite solved the crazing problem - the usual approaches (lithium, mangnesium) weren’t working well and I ran out of ideas. There is perhaps still potential using manganese in other bases, see Jewel Tone.

Nickel-Barium Purple

Around this time, David Tsabar published a very promising high-fire nickel purple recipe. While some previously published recipes appeared to have a browning tendancy, this one was unmistakably and consistently purple.

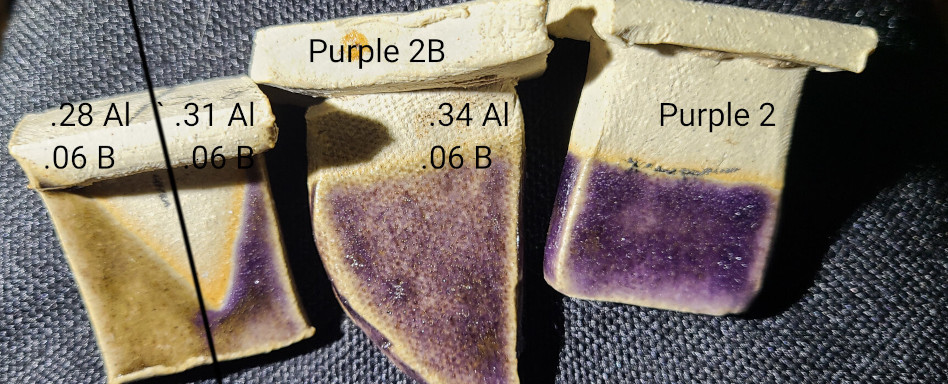

I fired David’s recipe at cone 9, and was encouraged by the immediate impressive results. Anticipating poor melt at cone 6, I tested slight additions of borax to see how the color responded. Previously, in my manganese tests, any amount of boron killed the purple, but it appeared to be potentially useful for adjusting the nickel-barium recipe.

Adjusting for Cone 6

Some initial ideas for improving melt:

- Add boron to bring down melting point

- Use barium frit instead of barium carbonate

- Introduce a super melter like bismuth

I gave up on boron almost immediately. Borax is soluble in water and therefore not a practical source of boron; it is usually instead sourced from a calcium borate frit or a borate mineral. Introducing any alkaline earth flux like calcium or strontium turns the purple to brown, making it difficult to find a material that fits the constraints. Pemco Frit PC-4X63 is a calcium-free boron frit that can be purchased in small quantities in the United States.

Finding a barium frit is even more challenging. Barium is largely obsolete in studio pottery, as its toxicity limits its use in foodware, and in 90% of cases, strontium serves as a viable substitute. Ferro used to manufacture a barium aluminosilicate frit but it is utterly impossible to find today. Any barium frits available today appear to be formulated for ceramic tile glazes, containing either zircon opacifier, or other prohibitive fluxes. Degussa 90420 would likely work, but I have no way of obtaining it in the United States.

The third option, bismuth oxide (Bi2O3), is a rarely-used super melter that is similar to lead oxide (PbO) in some ways, without the toxicity.

A few problems are apparent but not insurmountable:

- Too runny - decrease bismuth

- White specks / pitting - improve melt, strain better

- Glaze is matte were thin - increase silica or decrease surface tension

Adjusting the fluidity was easy and I settled on 4.1% zinc oxide and 3.2% bismuth oxide.

Attempted Gloss Adjustment

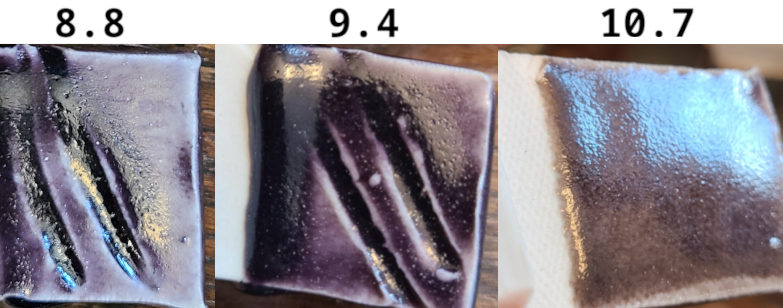

David’s tests at cone 9 indicated that introducing silica without changing other variables improved the glossiness, so I tried something similar, adding even more silica in small increments.

This line blend reveals two things:

- A consistent gloss appears around 10.7 SiO2:Al2O3

- Exceeding 9.4 SiO2:Al2O3 destroys the purple.

Unfortunately, this means there’s not an obvious next step to tune the gloss. The next few tests use the maximum silica that doesn’t turn the glaze black.

Eliminating Unmelted Specks

The glaze contains about 30% barium carbonate, which is likely difficult to melt and causing the white specks seen in previous tests. I was able to eliminate the specks by replacing the sodium source (nephaline syanite) with Fusion Frit 644 (65% SiO2, 6% Al2O3, 29% Na2O). Now that 10% percentage of the glaze is essentially pre-melted, this should give the barium more time to incorporate into the glass. After this adjustment the specks seems to have disappeared. I also started straining the glaze through a tighter 200 mesh sieve after this point but it’s unclear if this was necessary.

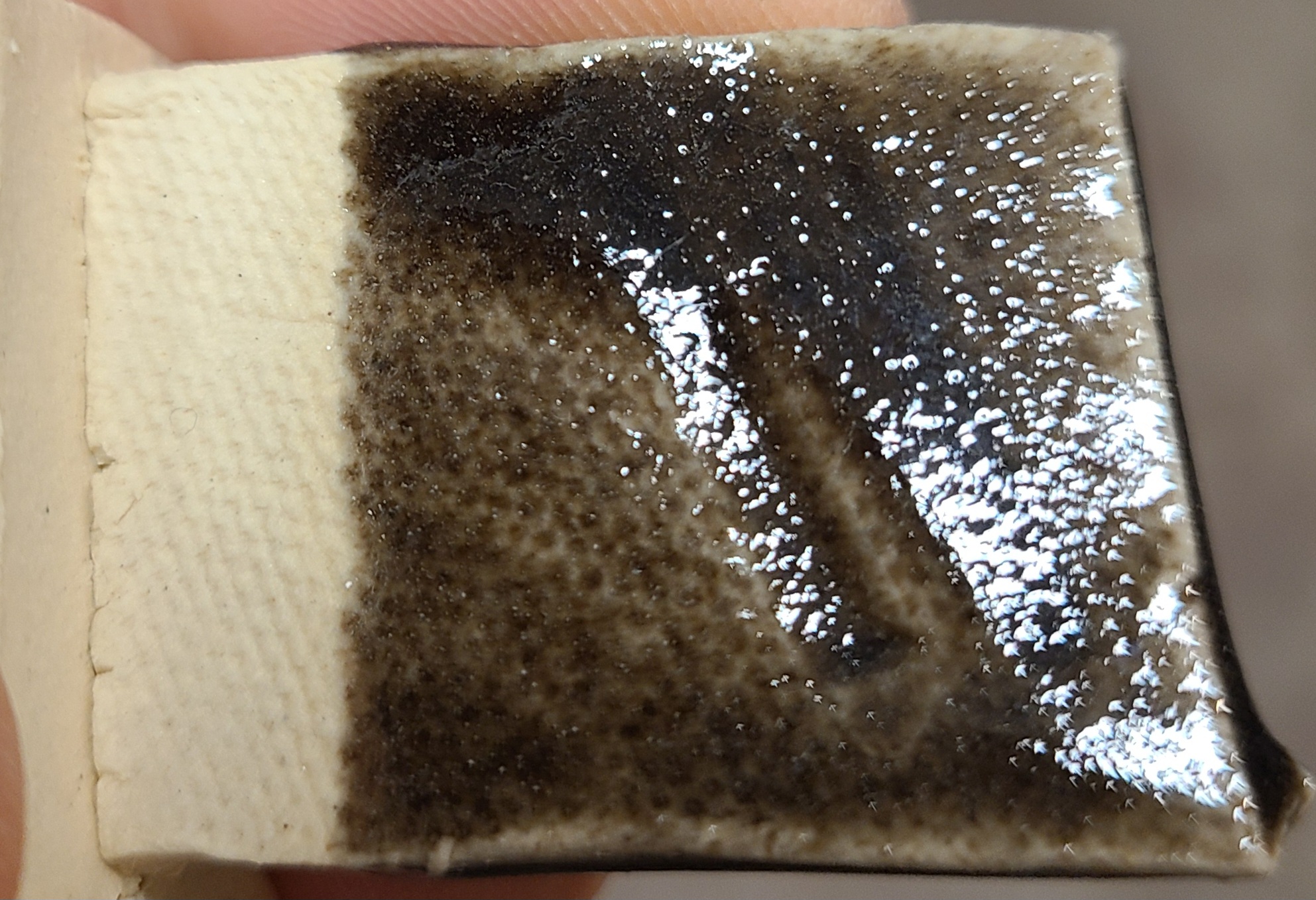

Checkpoint - Cone 6 Nickel Purple (Satin)

The glaze now seemed good enough to use. The piece pictured has it brushed on sloppily, and despite the thickness variations, the surface texture is a nice consistent satin. It does not craze on any clay bodies that I’ve tested (Standard 365, 240). The color is very sensitive to thickness and it should probably be sprayed or dipped for consistency.

| Material | Percent |

|---|---|

| Barium Carbonate | 30.30 |

| Silica | 29.30 |

| New Zealand Halloysite | 22.50 |

| Fusion Frit 644 | 10.60 |

| Zinc Oxide | 4.10 |

| Bismuth Oxide | 3.20 |

| Total Base Recipe | 100.00 |

| Black Nickel Oxide | 1.40 |

| Cobalt Carbonate | 0.05 |

| Total | 101.45 |

Adjusting Surface Tension for Gloss

The satin glaze is nice but ultimately I want something perfectly glossy. I use a slow cool schedule in my kiln which probably isn’t helping. It might be worth testing a faster schedule to see if it’s glossier, but given that even the original cone 9 recipe appears to develop matte spots, I’d prefer to find a way to solve this chemically.

Tony Hansen points out on this page that fluxes vary in their contribution to the surface tension of a melted glass. High surface tension contributes to matting. Barium raises surface tension while sodium lowers it. Zinc oxide, despite increasing fluidity, actually raises surface tension, unlike alternatives like lead and boron. While his page doesn’t address bismuth, it seems like a good assumption that replacing zinc oxide with bismuth oxide would lower surface tension.

The next few tests will attempt to replace some high surface tension fluxes with lower surface tension fluxes while modifying the silica to retain the color.

Zinc Removal Test

In this test, 4.1% zinc oxide was replaced with 2% bismuth oxide. I also simultaneously tested Fusion Frit F-413 in place of the 644 (with the appropriate chemistry adjustments). This was probably a mistake as it introduces another variable.

The test tile has a quite glossy surface, lending credence to the surface tension hypothesis, however, it also came out black (and orange-peeled, but that’s a future problem). The white specks are back, which could be an indication that this frit takes longer to melt.

This test at least raised the possibility that zinc is important for color development. Future tests should retain some zinc and adjust another variable to find the threshold where color is lost.

Sodium vs. Barium Test

An easier test is to substitute some barium, the main culprit behind the matte finish, with sodium. Anticipating issues with color, I did this as a biaxial against silica.

TEST IN PROGRESS 1/23/2026

On one axis, barium is gradually replaced with sodium, and on the other, silica is decreased to the left and increased to the right.